Episode 4: When You Talk About Tourists, You Talk About Me

In Choki Dhani, In Jaipur, In India

I have always been unsure about my relationship to where I come from.

But on our most recent trip to my homeland of India, I realized that I am no different than a tourist, albeit a glorified one, but nonetheless someone whose connection to the place is surface level at best.

I don’t feel particularly attached to India as much as I did as a kid, when we would spend summers there in the same home my mother grew up in a small town called Modinagar. I still hold fond memories of foggy mornings in the courtyard of my mother’s home, watching the cows find their ways into the alley just outside the entrance, and the evenings where my cousins and I would retire to gigantic beds with the thickest and heaviest blankets I have ever encountered, their weight alone putting us to sleep within minutes.

My memories linger partly because many of the people I broke bread with, the aunts and uncles who are no longer with us.

As I went back on my own in college and after, these memories sit idle against recent experiences, including the trip I took this past winter. Winter in Delhi, and its suburb Noida (where much of my family lives now), means severe pollution and sub-40 degree temperatures. What this means for me is that our short time there feels almost like visiting another planet.

As an adult now, with two kids who were as old as me when I started going regularly to India with my parents, I want them to have idyllic memories (like I do) filled with tender fog and bracing whatever could be braced in diesel vans winding their way to hill stations and sweet rasgullas. But I also know the experience for them will be vastly different, and what they retain will be all their own.

And I also strive for to be honest with my children about what India is like now for me, because it’s changed so much.

I can go on about the rise of Hindu nationalism, as well as the adoption of its logic by my family. In a trip we took just before the COVID pandemic shut everything down, I got into discussions with relatives about the recently enacted Citizenship Amendment Act, BJP, RSS, and Prime Minister Narendra Modi. No logic would dissuade them against the lionization of the status quo.

Only later did I realize that because belonging and community root within our very guts, they could not be moved.

So I stopped talking about it. Maybe that is cowardly, maybe that was just to not brew further bad blood. Or maybe I was tired. Yet soon after, we got on a plane to Bangalore where politics didn’t come up as much.

So we designed our December 2023 trip to be a bit more touristy, a bit more like what I remember.

We did that also because without a destination, my family would stay in their pajamas all day, especially the kids.

One of the trips we took was to Jaipur. The first night, we took our car to Choki Dhani, a tourist trap just on the edge of the city meant to showcase all the delights of Rajasthan. It took one hour for us to get there from our comfy hotel, but making the necessary U-turn into a busy intersection to get within a stone’s throw of the entrance felt like an eternity.

As soon as our van let us off on the street, we dashed to the entrance like children let out on the last day of school. We got caught up in the bustling crowd elbowing other ticket-buying desis sporting American accents and kurta pajamas. The place was dimly lit, and my partner was skeptical of the whole affair; I was simply going along with what my aunt and cousin wanted us to do, and I hadn’t seen them for four years, so I obliged.

My aunt’s son, the one who is younger than me and the one whose life I most often think about when I think about India and has two kids like me, wanted to take us to Choki Dhani.

But as luck always has it, we can never coordinate a trip out together.

Since the advent of children and wage labor, coordination evades most parents’ grasp as various school, medical, or other obligations get in the way. Which is what happened in this case, my cousin planning out the details of our trip, but unable to attend.

We felt a wave of relief when we finally got into the place, and went straight to eat.

After a meal where our children engorged themselves on rotis and jalebis, a sense of urgency came over me as I realized that the night was marching on, and we had to make the most of the place. We saw a beautiful performance by a woman who held stacked pots on her head, fire coming out of each pot. She held those pots up with such dignity, a smile beaming across her face. Just from looking, I could tell that she took pride in this work.

At the end of her performance, she beckoned people to dance with her, and a few of us went up. But as I saw the dancers, their faces blank in stark contrast to the main performer whose infectious smile, even while walking on coals, lit up the night.

After that, I kept looking at peoples’ faces. Many performers were clearly unhappy with the work. I’m not sure how many of the workers were Rajasthani, but I can see how doing these performances, serving people like me, day in and day out, was beyond tiresome.

This is modern tourism, and I shouldn’t have been surprised. And it is apt for a tourist to want to maximize our time there. The difference here is the show is starkly different from other shows, other parks I’ve been to in that you can see the worker’s distaste. My aunt told me that they keep raising admission prices to Choki Dhani, but it’s unclear if the workers see any of that. Some of them are even prevented from asking for tips.

My partner and I looked at each other while trudging through the sand on the ground (likely to mimic the Rajasthani desert) that constitutes the grounds of the place, instantly recognizing the problem with our current predicament. We were here to see something authentic, on recommendation from a dear and close relative, but what we got was a precisely authentic slice of modern capitalism.

Even the animals aren’t safe from exploitation. While gawking at the sites, we almost got run over by horse drawn buggies, camels, and elephants. The kids really wanted to go on an elephant, but when we did, we all felt icky afterward. The elephant looked weary, walking in sand compressed by its own weight because it walked the same 10 meter path hundreds of times a day, hauling people like us with more people like us pointing phones and cameras at the bejeweled beast on each tiny round trip.

At that point, my sister and my parents and aunt and kids also felt strange about the place.

But the curtain hadn’t yet fully opened to reveal Choki Dhani’s furious underbelly. We had already decided that this was to be a quick trip, and seeing what we had already seen resolved it for us. But on the way out, I saw men, seemingly drunk, get up on the mini stages to engage in bad dancing with women who were goading them on. Of course, the dancers were paid to do this, but the men couldn’t help themselves to pelvic thrusts and other predictable movements, each move inching them closer to the performers.

That is when it became clear that Choki Dhani was a place to fulfill men’s fantasies, which is another way of saying that tourism is about further entrenching the control that men have over time and space.

My only regret is that we ended up going there at all, rather than explore some of the pink city’s evenings, like grabbing an onion kachori or seeing the kids’ faces reacting to Hawa Mahal’s edifice sparkling at night.

But this reminded me that I am just a different shade of those drunken men. That when I visit India, I too am a glorified tourist. I don’t understand the culture fully, as much as I would like to. I don’t get the social mores and requirements as much as I probably should. I don’t know how to delicately thread the needle on political issues in a place that is lurching towards fascism. As an American man I can take over the time and space in most places in India, and could dominate it - if I wanted to.

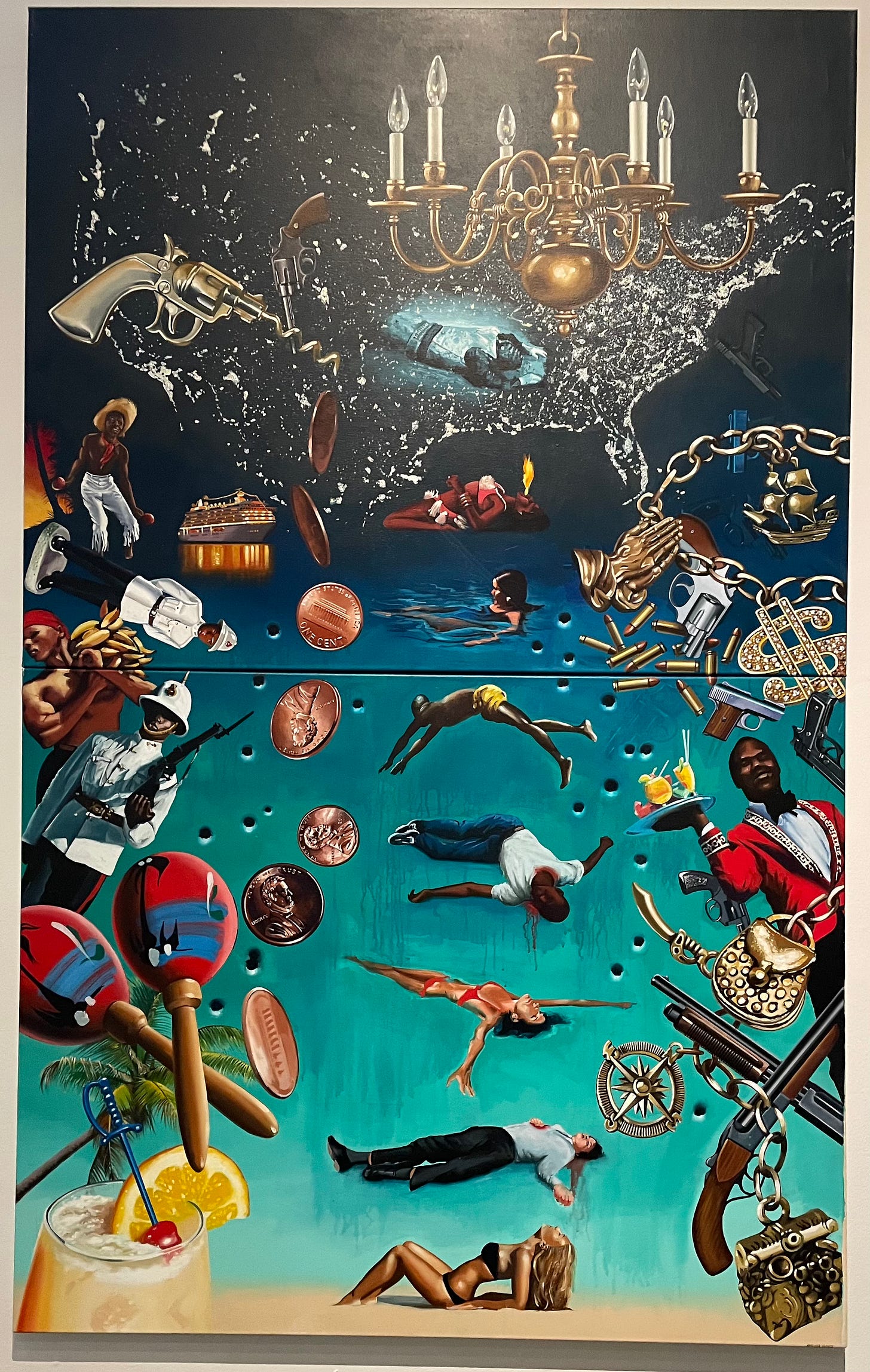

A few months prior to India, I went to Puerto Rico with my partner, where we attended an exhibit called Tropico es politico, and saw this beautiful work by Dave Smith. I thought of this painting because fire plays an important role here, just as it did with the dancer - both essential to the spectacle I witnessed in Jaipur, as well as the allure of women, money, leisure, and its tie to labor. Here, though, we can see the waiters smiling, the performers dancing, but juxtaposed against guns and dead bodies, we see the deep price of tourism.

While I was in line for a Rajasthani thali at Choki Dhani, a high school kid clearly from the United States peppered his mom with queries as she blindly deposited food onto his plate, “What is this? I don’t know what this is?! What am I eating?” I too should have asked these questions long before Choki Dhani, probably even long before stepping onto the plane. Nonetheless, this was the place that clarified for me what I already felt - that to be me in India, is to be a tourist.

How do you feel when you travel to your homeland? Does it feel something like what I described? I’m curious. Leave a comment!

I’ve not yet made the trip with the kids to India or Bangladesh. I too feel like a tourist every time I’ve been to either place as an adult. I’d like to plan the trip with my parents because it feels less like a tourist destination and more like an excavation of memory if the kids can imprint memory to a place.

I feel like this when I go to the Philippines! Wanting connection to my homeland, but always feeling conflicted for similar reasons. American is written all over my face and I cringe at what is considered entertainment. I am definitely an outsider. I want to feel more tender things like the memories I have of taking my baths in a galvanized steel tub during a brownout, but those days are gone. Or perhaps it’s all nostalgia.